The Railroad

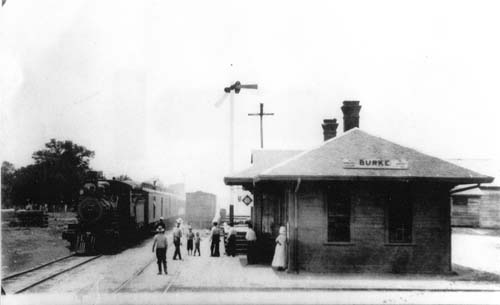

The Old Burke Depot

Above all else Burke is dominated by the railroad, and it owes its existence to Houston East and West Texas Railway, which arrived in 1881. Later it became the Texas and New Orleans Railroad and then Southern Pacific Railroad. Today the railroad is owed by Union Pacific Railroad.

The railroad played a huge role in the life at early Burke. For 40 years after the railroad reached Burke, it was the only way to travel long distances and to ship agricultural products to market. One of the main reasons for building the railroad was to gain access to the cotton, livestock, and timber produced in East Texas and needed in growing cities such as Houston.

Passengers embarked and disembarked at a depot which was located on the west side of the tracks adjacent the School Road and catercorner from the post office. Franklin Weeks' grandparents (James Monroe Weeks) honeymooned by traveling by train from Burke to Lufkin and back. After the depot was torn down, it was replaced by a small open building providing shelter for passengers and a storage area for mail. In addition to the depot for passengers, there was also a loading chute for hogs and cattle directly in front of the post office.Not until Texas Highway 35 was built in the mid-1920s did the railroad begin to decline as a means of travel.

The train also brought mail to and from Burke. The postmaster would put all outgoing mail in a sack and hang it from an elevated arm beside the depot. The train would snare the sack as it passed by.

Train Excitement

The arrival of the railroad brought excitement and entertainement to this rural corner of East Texas. People came from far and wide to see the train huff and puff into town and discharge passengers. Amos Spears, whose granddaughter Florence Largent Johnson lived at Burke most of her adult life, brought his family from the Zavalla area to Lufkin to see the train, and they liked the area so much they sold out and moved.One Burke area rural resident, who had never seen a train, came with her mother to Burke to visit the dentist, Dr. Johnston. When the train passed through Burke, the frightened girl ran and jumped into her mother's lap while Dr. Johnston was working on her teeth.

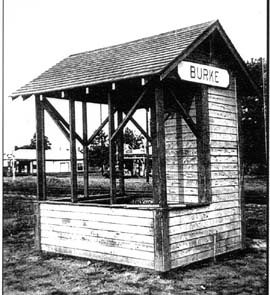

After the old depot was torn down, it was replaced by a small, open-sided shelter with an enclosed room for mail.

Burke Passenger Shelter

There was always an ambivalent attitude toward railroads, which were the only big business presence in a community of farmers. Railroads were vital but not always loved. That ambivalence was expressed in the humorous phrase that was attributed to the railroad's initials -- "Hell Either Way You Take It."

Mr. Bremond's Road

The railroad was built by Paul Bremond, a Houston railroad builder and financier. A native of New York, Bremond moved to Galveston in 1839 after his New York and Philadelphia hat business failed in the Panics of 1837 and 1839. He ran an auction and commsissions business in Galveston, but he quickly recognized Houston's potential and moved to that upstart city in 1842, where he began to build railroads. Before the HE&WT, Bremond was involved with several railroads, including the Houston and Texas Central to Dallas.

Despite his family's Episcopalian religion, Bremond was a spiritualist; and he believed that he was spiritually guided by a soldier in Texas Revolution, Moseley Baker. Bremond himself stated that he was motivated by Baker's sprit to build a new railroad. He obtained a State charter in 1875 for the Houston, East and West Texas Railway, to run from Houston to Shreveport through the East Texas piney woods. The railroad came to be know as "Bremond's Road."

Bremond's other roads were standard gauge, but he became enamoured with narrow gauge railroads by the time the ghost of Moseley Baker spoke to him. He was convinced that narrow gauge was the secret to economically successful railroads on secondary routes such as that through East Texas. So the HE&WT was originally narrow gauge, but Bremond's judgment proved wrong, and it was later converted to standard gauge.

Routing the Railroad

The reason for the route followed by the railroad through Angelina County has always been a mystery, and the information vacuum has been filled by myth. At the time the railroad was planned, the county seat of Angelina County was Homer, which is now a small rural community that lies about 6 miles southeast of Lufkin. Homer enthusiastically supported the railroad, and one would have expected the railroad to pass through Homer rather than through Bradley Prairie and then Denman Springs, which later became the site for Lufkin.

The Drunk Survey Crew Myth

The myth states that the railroad route originally was to pass through Homer, but it was changed after members of the survey crew were arrested and jailed for drunkenness at Homer after unwinding from a long week in the wilds of Angelina County. Angered by the arrests, the story goes, the survey crew chief went back to te Neches River and resurveyed the railroad route farther west through the farm of a friend at Denman Springs with whom he was staying, thus dooming Homer and launching Lufkin on its rise to prominence.

Most debunk the story, but it is persistent. It led to a gloss on the myth at Burke that the route change happened at Burke resulting in the westerly curve on the railroad north of town. This addition to the myth is eaily disproven by simply looking at a map and observing that a northward projection of the railroad from Burke would have intersected Lufkin near the US 69-Loop 287 intersection, which is substantially west of Homer. The railroad would have had to curve eastward to reach Homer.

The Real Story Behind the Route

Some debunk the arrest story by referring to the prospectus for the railroad printed in the late 1870s which shows the railroad following the current route. The story is probably even more complex.

Routing a railroad is an economic compromise among local support for building the road, minimization of cost by using the least steel possible and maximizing revenue by servicing the best paying customers. Local support in the case of the HE&WT was in the form of "subscriptions". This included everything from direct payments by merchants to donation of land for rights-of-way and terminals to provision of services to clear and build the road bed. The HE&WT was built on a shoestring and was mostly funded by Bremond himself. The road therefore required all the community support it could get, and subscriptions by wealthy locals probably spoke loudly in determining the route.

Everyone had their idea where the railroad should go. A story in the Galveston News in October, 1876 advocated extending the the railroad northward from Moscow and crossing the Neches River just south of the mouth of Piney Creek on the Polk-Tyler County line before continuing on to Homer. The advantage of this route is that it would cross the Neches River at the crossing for the old Nacogdoches-Liberty Road near the old Spanish settlement of Fort Teran. That is where the limestone formation known as the Kisatchie Wold crosses the Neches, providing both a hard bottom to the river and a gap in the hilly travel barrier of the Wold. The disadvantage is that the route would have been well to the east of Homer and would have required a sharp turn west to reach Homer. Of course, this would have benefitted the timber interests of eastern Polk and Tyler Counties.

The original plan might well have been to extend the route directly from Moscow to Homer since the Galveston News in 190__ quoted the railroad surveyor as saying that the original route to Homer proved impractical. A glance at a map shows the problem. In that area the Dollarhide Cutoff, an old branch of the river, forms a very large island that extends for several miles downriver. Crossing in this area would have required two large bridges and would have probably traversed substantial swampy ground. To this day there is no settlement near the river in that area, and most early access to the river lay west of the ultimate route indicating that the terrain was more favorable to building a bridge and roadbed. The railroad was rerouted up the river crossing just west of the start of the Dollarhide Cutoff, near the site of Clark's Ferry and an established route to Polk County, which had been in existence since 1856.

The jailing of the survey crew myth and the unsuitableness of the direct route to Homer notwithstanding, the real explanation for the westerly route probably lies with Washington Lafayette Denman. Mr. Denman was clearly an influential and relatively wealthy man. In 1870 he reported real estate and personal property worth $12,500, which equates to about $200,000 in current Dollars. He ran a sawmill as early as 1877, and and he was variously referred to in the newspaper as "Hon." and "Col." indicating a high status in the community. Furthermore, his son, Alexander Madison Denman, was an early Angelina County physician.

Mr. Denman was one of the primary promoters of the railroad in Angelina County. At a barbecue and public speaking at Homer in May, 1877 to promote the railroad in the County, he served as the master of ceremonies. The Homer myth also states that the survey chief stayed in Mr. Denman's home during the time he was in the county. If the reports that Burke was named for the "civll engineer" who surveyed the railroad are true , the crew chief would have been Edmund Burke, son of prominent Houston merchant and railroad investor Andrew J. Burke.

Oddly the railroad wound up passing through Mr. Denman's property at his home at the community known as Denman Springs. The unsuitability of the direct route to Homer, though plausible, may have been a cover story for Mr. Denman's economic interests, and the jailing of the survey crew story, which could have had some basis in fact, may have been a case of sour grapes by the citizens of Homer bypassed by the economic miracle of the Houston East and West Texas Railway.

Clearly, the westerly route economic advantages for promoters of the railroad. Not only did it run through Bradley Prairie, considered one of the better agricultural areas in the County, but it also provided the railroad the opportunity to promote an entirely new town, Lufkin. Undoubtedly Mr. Denman's subscription to the railroad was to donate land for a townsite,knowing that the value of his surrounding land would increase tremendously. Paul Bremond, the President of the Railroad, was deeply involved in the sale of lots in Lufkin through his son Edward L. Bremond, and a Lufkin street is named for him. Mr. Denman's sawmill interests also pointed to an industrial future for the area, which would prove more profitable to the railroad than serving the farmers. In his promotional pieces, Bremond prominently referred to the timber and mineral resources of East Texas as a reason for building the road.

Sources:

- Handbook of Texas Online, "Houston East & West Texas Railway"

- Handbook of Texas Online, "Texas and New Orleans Railroad"

- Handbook of Texas Online, "Paul Bremond"

- "Railroad News." Galveston News, October 13, 1876

- "Railroad Meeting and Barbecue at Homer," Galveston News, May 17, 1877

- Fayette Denman, 1870 Angelina County Census

- Lafayette Denman, 1880 Aangelina County Census

- Lindell Harris, Personal Recollections

- M. Lee Murrah, Personal Recollections

- Franklin Weeks, Personal Recollections

- Pine Bough, September, 2001 (The History Center, Diboll, Texas)