Cattle Raising

Before Cotton and Timber

East Texas is not normally thought of as cattle ranching country. The cowboy myth locates the Texas cattle industry in South and West Texas with their giant ranches, such as the legendary King and XIT Ranches and celebrates the great cattle drives along the Chisholm Trail to Kansas and beyond. The tangled woods of East Texas do not seem conducive to the cattle. It would seem that cattle raising would have become possible only after the latter day practitioners took over the open ground of the abandoned farms that had been hacked from the dense forest in the late 19th Century.

Nevertheless, before railroad and its economic progeny, the timber and cotton industries, cattle were the primary cash crop in Angelina County. Contrary to expectations, East Texas is actually where the Texas cattle industry began. The Handbook of Texas observes that

Before the war [Civil War], a principal source of wealth in Angelina County was the raising of livestock, since most of the early settlers were not slaveholding planters able to concentrate on agriculture.

Every farmer, of course, had at least a milk cow and perhaps a few beef cattle to supply their own needs. Many practiced a balance between farming and cattle raising that is "farmer-stockman" lifestyle. It can be traced back to the Atlantic Coast, especially South Carolina, and it spread across the South until it reached East Texas in the early 19th Century.

A few, the "cattle keepers", concentrated primarily on cattle raising and driving them to market along early cattle trails through the East Texas woods.

Origins of the East Texas Cattle Industry

According to writer Randy Mallory, the East Texas cattle industry traces its origins to the early Spanish explorers and missionaries.

Some cattle escaped the mission and, during the next century, produced a prolific progeny: thousands of black, long-horned Castilian cattle roaming free along the Neches and Trinity riverbottoms. By the time of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, westbound American settlers were drawn to Texas' fertile soil and fabulous cattle.

Mallory further noted that

An Ideal Cattle Environment

Despite popular perceptions of western ranches on the wide open plains, East Texas is actually a much better enviroment for cattle raising. The larger annual rainfall in East Texas promotes the growth of grass and forage, and the rivers and oxbow lakes provide plenty of water. The cane breaks and palmetto fields in the river and creek bottoms provided winter forage. East Texas can support more cattle per acre than any other part of the state.

According to geographer and cultural historian Terry Jordan the cattle culture of the South was concentrated in the longleaf pine band that extended from the Carolinas to the Piney Woods of East Texas. The tall, straight longleafs grew relatively far apart permitting tall, lush grasses to grow beneath them and providing plenty of space to herd the cattle. The cattlemen continued the practice developed by the Indians of burning the grass each winter to fertilize a new crop of grass the following spring. The pines due to the height of their canopy were resistant to most grass fires.

A portion of the longleaf pine belt ran through southern Angelina County along the north side of the Neches River, including Pine Valley.

Angelina County geography also made it an ideal place to raise cattle. Before the invention of barbed wire, cattle were allow to run on the "open range". They were simply turned loose in the woods and permitted to fend for themselves and wander wherever their grazing took them. Farmers were required by law to fence in their crops to keep the cattle out. It was not uncommon for cattle and hogs to wander into nearby towns. The open range continued in some counties in southeast Texas until the 1950s when the practice was outlawed by state law. The author recalls driving through parts of Polk County where motorists were warned of the cattle by road signs.

In the open range era, the Neches River provided a barrier to the south while the thick loblolly and hardwood forests in the northern part of the county provided a northern barrier. The water in the river and the nearby sloughs, swamps and oxbow lakes provided water, which provided further reason for the cattle not to wander too far to the north. All these factors together created a southeast-northwest corridor for cattle migration and cattle drives.

The Early Stock Keepers

As settlers moved across the South, the cattlemen preceded them. By 1810 they had reached southern Louisiana and by 1845 they had reached Angelina County. The undoubtedly followed the "road" provided by the longleag pine belt and were probably attracted to East Texas by the ready supply of wild Spanish cattle that were free for the claiming. Undoubtedly they brought their own English breeds with them as well.

The early cattlemen in Angelina County referred to themselves not as ranchers but as "stockkeepers". The term "stock keeper" is unusual, and it reflects akey difference from the later "ranchers" of South and West Texas. Ranchers ran their cattle on vast tracts of land that they owned and later fenced with barbed wire. They needed large tracts because the dry climate of West Texas would not support a high livestock density. Stockkeepers did not need as much land because the wet climate of East Texas permitted more cattle per acre. The cattle keepers owned land but still not enough to support hundreds of head of cattle. Instead they followed the "open range" model of the Deep South in which cattle were allowed to roam free through the woods and swamps.

Southwest Angelina County was ideal for open range cattle operations. The long leaf pine savannahs provided plenty of open ground from grass, and the river bottom provided cane breaks for winter forage and plenty of water. The low-lying, swampy land north of the Neches River provided a large amount of land that no one else wanted for any other use, which was ideal for open range cattle operations.

The Angelina County Census of 1850 lists the occupation of several families in the southwest part of the county using that phrase. In southwestern Angelina County, these include:

- Robert Myers

- James Ashworth

- Eli Ashworth (son of James)

- Crawford Ashworth (son of James)

- James Ashworth, Jr. (son of James)

- J. F. McFaddin

Cattle Breeds

We do not know for certain what type of cattle the cattle keepers of Pine Valley ran, but we can make a good guess.

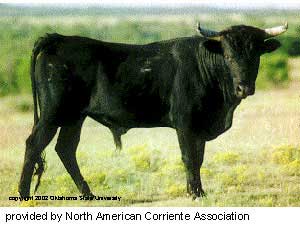

The first cattle brought to East Texas were of the Spanish variety. Many of these cattle escaped from the explorers' and missionaries' herds, creating herds of wild cattle along the Neches and Trinity Rivers.

The Spanish cattle were already running wild in the East Texas bottomlands when cattle keepers arrived from Louisiana and the Deep South, and the large herds of "free" cattle may have been one of the factors that drew them to East Texas. The cattle keepers also brought their own English cattle, which were probably of the English longhorn variety prevalent at the time. The English longhorn is

The English longhorn is reminiscent of the oxen seen in early East Texas logging pictures, and it is likely that many of these large, strong animals were used for draft purposes. Oxen were not a separate breed but were usually castrated males of any cattle breed.

According to some historians, these two types of cattle eventually mixed, creating the modern breed known as the Texas longhorn.

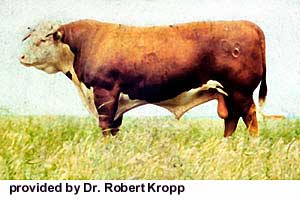

In the 1870s Texas longhorn cattle were driven to Kansas in the legendary trail drives. Unfortunately, the hardy longhorn carried a tick-born disease known as "Texas Fever" that devastated domestic breeds, making them unwelcome in Missouri and Kansas. Further, beef markets in the East began to prefer tender beef marbled with fat, which the tough, lean Longhorns could not provide. As a result longhorns became unpopular with Texas ranchers, and they began to import beefier English shorthorn breeds such as the Hereford.

In the Twentieth Century the Hereford and other breeds, such as the Brahma, proliferated, and the old Texas breeds disappeared. It is likely that the old Texas breeds lived on into the Twentieth Century in the mixed breeds that many small time farmers ran. The Webmaster recalls cattle belonging to his father who had characteristics of the earlier breeds.

Roundups and Cattle Drives

Twice a year the cattle owners would go on "cow hunts" to find their herds and brand the new calves and castrate the yearlings (or "fix" them as the author's father politely referred to it). In the Deep South they had done this on foot, but in Texas the cattlemen had adapted to the Spanish custom of herding cattle from horseback. However, they still used their cow dogs and bull whips to control the wild open range cattle. Cow hunts were often dangerous The author's third great-grandfather, Patrick Johnson, who came to Pine Valley along with the Ashworths in the 1840s, was killed in 1868 on a cow hunt or cattle drive at Lovelady in Houston County.

The cattle keepers were commercial cattlemen, and they needed a market for their cattle. Since there was not transportation, the cattle keepers drove their cattle to market along the Opelousas Trail. The early market was in New Orleans, and cattle were driven eastward. Later when railroads reached Kansas, flow on the trail reversed as cattle were driven westward to Ft. Worth and thence north to Kansas for shipment to the heavily populated East Coast. The East Texas cattlemen who were already familiar with cattle drives to Louisiana along the Opelousas Trail and others helped pioneer the great cattle drives up the Chisholm Trail to Kansas.

The Decline and Rebirth of the Cattle Business

When the railroad brought an economic way to get their product to market, it also brought cotton farmers, who quickly displaced the cattlemen. Large scale farming shrank the open range, and the lumber companies cut the great longleaf pines of Pine Valley.

The cattlemen moved on to South Texas and became pioneers of the classic Texas cattle ranch culture that developed in such places as Bee and Nueces Counties. Among those who moved on to South Texas was Jordan Perkins, brother-in-law of James Ashworth. It is also likely that the Ryan brothers, founders of Ryan Chapel Methodist Church, also followed the cattle frontier to Karnes County.

Ironically as farming declined in importance after World War II, cattle raising made a comeback in Angelina County and Burke. Farmers converted their former cotton fields into cattle pastures, and many raised cattle as a sideline after they began working in the industrial mills. Major farmers and cattlemen in later years included Roy Treadwell and Bloomer McCall. Those who kept their hand in farming, such as Hillary Thigpen and Corbett Conner, raised hay and hired out their tractors and machinery. Hillary Thigpen also raised hogs. Some such as the author's father, Elroy Murrah, took jobs in industry but continued to raise cattle on the side. dd gsdfgsdfgsdfgsdfgdfsddddd

Today East Texas is again a a major player in the center of the Texas cattle industry. Ironically, most farming is now done on the high plains of West Texas.

Sources:

- 1850 Census, Angelina County

- History of Angelina County (Curtis Publishing)

- Patrick Landrum, Personal Recollections as told to M. Lee Murrah

- Bruce M. Shackleford, "The Texas Longhorn: Where They Came From and Where They Went", http://www.texancultures.utsa.edu/hiddenhistory/Pages1/shackelford.htm

- "English Longhorn Cattle", http://www.rarebreeds.co.nz/longhorn.html

- M. Lee Murrah, Personal Recollections